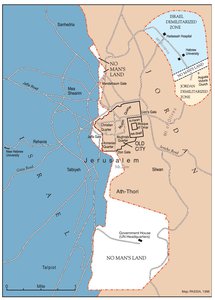

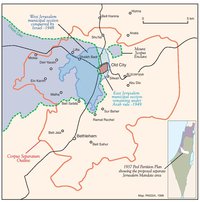

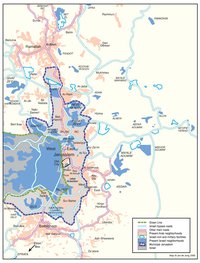

PARTITIONED JERUSALEM, 1948-1967

Map Details

Two months after the Jordanian Arab Legion entered the eastern portion of the city, Israeli forces failed in a

final bid to storm the Old City and fighting stabilized along a frontline bisecting the heart of Jerusalem. In

late November 1948, Moshe Dayan – commander of the Israeli forces in the Jerusalem area – and his

Jordanian counterpart Abdullah At-Tal signed a “complete and sincere cease-fire.”

The crudely drawn map accompanying the cease-fire and demarcating the two sides’ respective positions in

the city was later described as a “cartographic monstrosity.” It was never intended as the ultimate word on

the division of Jerusalem, but when Israel and Transjordan signed the Rhodes Armistice Agreement in April

1949 it was made the sole point of reference and so defined the partition of Jerusalem until 1967.

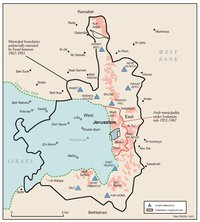

The thick lines drawn by the two commanders had the unanticipated effect of creating an unclear and arbitrary

no-man’s-land of between 60-80 m in width running north to south through the city. Some 125 homes

were stranded in this ambiguous and unmarked ca. 850-dunum zone, surrounded by 55 fortified positions.

A single crossing-point, at the Mandelbaum Gate, allowed UN Truce Supervision (UNTSO) staff to monitor

the two sides’ compliance with the armistice. The provisions of the armistice included access for a biweekly

convoy of supplies and staff from West Jerusalem to the demilitarized enclave that Israel had retained around

the Hadassah Hospital and Hebrew University on Mount Scopus in East Jerusalem. UNTSO, along with other

UN bodies, established headquarters in the old British Government House to the south of the city, creating

there an additional no-man’s-land area. The no-man’s-land strip was eventually fenced on each side in

1962, amid confusion and competition over the exact location of the lines. In all, the dividing area

represented 4.4% of pre-1948 municipal Jerusalem. To the east, Jordanian control extended to 11.48% of

the municipal area, while Israel controlled 84.12%.

Retention of its exclusive access to the Mount Scopus enclave meant Israel kept possession of virtually all

of its pre-war holdings in the Jordanian-held area – totaling 116 dunums. In contrast, the loss of Palestinian

land-holdings in the western (Israeli) section was total and vast. There, Palestinian pre-war ownership

amounted to 5,544 dunums, or 33.7% of the West Jerusalem area. Religious endowments and public

ownership made up 36.3% of the area, while pre-1948 Jewish ownership accounted for the remaining

30%. In the city as a whole (East and West), Palestinian Christians and Muslims had, before 1948, owned

an estimated 11,190 dunums. By 1949, Palestinian private land ownership was reduced to 2,283 dunums.

As in Palestine’s other conquered towns and cities, once the initial mass looting and military requisitions

abated, West Jerusalem’s rich property spoils were divided officiously by the ‘Custodian of Abandoned

Property’ and its successor, the ‘ Custodian of Absentee Property.’ Government officials and senior ministers

were given ‘first pick’ of the elegant and luxurious Palestinian homes of the Talbiyeh, Bak’a and ‘German

Colony’ suburbs. The new Israeli Absorption Ministry meanwhile dispatched immigrants to possess the

‘lesser’ homes along the front-line areas and in the peripheral suburbs and villages. Between September

1948 and August 1949, at least 16,000 Jews moved into Palestinian Jerusalemite homes. In the village of

Deir Yassin, where over 100 men, women and children had been butchered in the most notorious massacre

of the war, an ‘immigrant camp’ was inaugurated. Polish, Rumanian and Slovakian Jews settled upon the

village land and took possession of the homes of the dead and the refugees; the site was renamed Givat

Shaul Bet.

Accurately quantifying Palestinian financial losses in Jerusalem has proven difficult and produced numerous

conflicting estimates. In losing the west of the city, and its outlying villages, the Palestinians lost that part

of Jerusalem where Mandate-period development had been focused and investment most high. The west,

home to Jerusalem’s wealthier historic families and new urban elite, had bridged the gap between the preserved

Old City and its less developed environs and the growing industrialization of the country’s economy.

In this regard, Jerusalemite Ruhi Al-Khatib, who was appointed mayor of Arab East Jerusalem in 1957, would

recall, “[o]ur heritage from the Mandate Government in this [eastern] part of Jerusalem was a distressed city

of shaking buildings, a paralyzed commerce and industry, devoid of any financial resources.”

By the end of 1949, Ben Gurion had moved the Israeli Prime Minister’s office from Tel Aviv to West

Jerusalem, declaring the city, “an organic and inseparable part of the State of Israel.” In the east, King

Abdullah of Jordan had resolved that, “Jerusalem is in our hands and will remain in our hands.” But such

declarations of sovereignty over Jerusalem went against the position maintained by the UN and the

international community. In November 1949, the UNGA reaffirmed its support for a Corpus Separatum

solution for the city, while the UK and US each issued statements acknowledging the current divisions, but

only, “pending a final determination of the status of the area.” The partition of the city was to stand until the

Israeli invasion of June 1967.

Related Maps

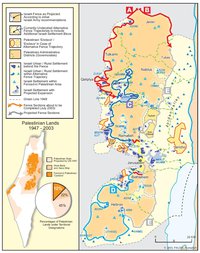

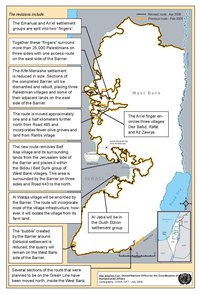

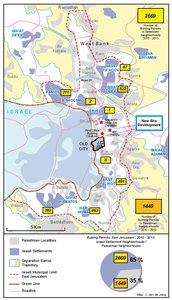

ISRAEL'S SEPARATION BARRIER, 2002

REVISED ROUTE OF THE ISRAELI SEPARATION BARRIER, 2006

THE OLD CITY, 1944 & 1966

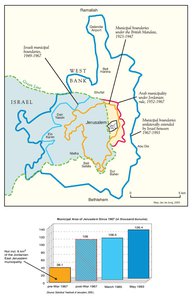

MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES OF JERUSALEM, 1947-2000

JERUSALEM AND THE CORPUS SEPARATUM PROPOSED IN 1947

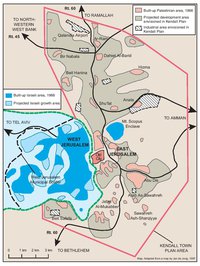

THE KENDALL TOWN SCHEME, 1966

JERUSALEM AFTER THE 1967 WAR

ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS AND PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS IN EAST JERUSALEM, 2000

ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS AND PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS IN METROPOLITAN JERUSALEM, 2000

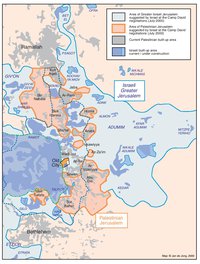

ARAB EAST JERUSALEM WITHIN ‘GREATER’ JERUSALEM, 2000

PROJECTION OF THE ISRAELI PROPOSAL FOR JERUSALEM’S FINAL STATUS AT CAMP DAVID, JULY 2000

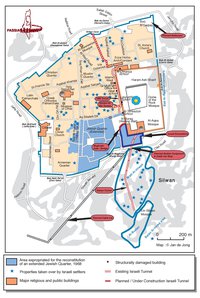

SETTLEMENT ACTIVITY IN THE OLD CITY

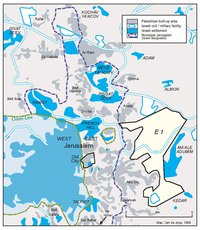

THE E-1 DEVELOPMENT PLAN

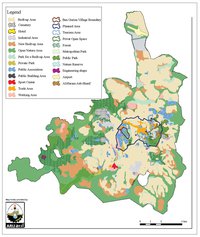

THE JERUSALEM MASTER PLAN

JERUSALEM TODAY (2014)