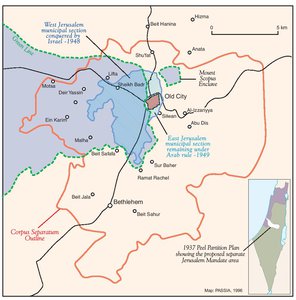

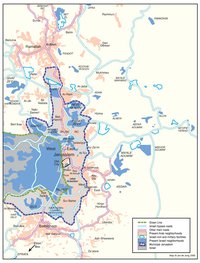

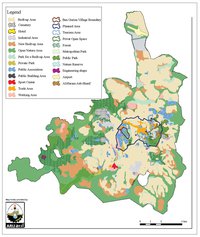

JERUSALEM AND THE CORPUS SEPARATUM PROPOSED IN 1947

Map Details

Mandate-period schemes for the partition of Palestine, beginning with that of the 1937 Peel Plan, isolated Jerusalem from the proposed Jewish and Arab states. They did so in recognition of the impracticable nature of any equitable partition of the city and out of a desire to prevent Jerusalem (and Bethlehem to its south) being drawn into the eventual arena of violent conflict; something the planners believed likely if not inevitable. Lord Peel’s proposal envisioned a permanent British Mandate over Jerusalem and Bethlehem, connected to the coast at Jaffa by way of wide corridor incorporating most of the Palestinian villages in the west of the Jerusalem district along with those in the Ramleh district. The British were to guarantee access to the two cities’ holy sites and protect and preserve these under the supervision of the League of Nations. The Peel Commission evoked the original Palestine Mandate document when it spoke of British rule over Jerusalem as “a sacred trust of civilization,” but made no clear provision for the involvement therein of the Palestinian and Jewish residents in running their own affairs: “This trust does not belong to the people of Palestine alone, but to the multitudes of people in other lands for whom one or both of these places [Jerusalem and Bethlehem] is sacred.” Subsequent partition plans, throughout the Mandate years, adopted the Peel formula for ‘internationalization’ (albeit under a British regime), altering only the territorial definitions of the proposed Jerusalem Mandate area. In the meantime, Britain struggled to contend with the administrative running of the capital. Jewish-Arab tensions, exacerbated by Britain’s 1937 arrest and expulsion of Jerusalem mayor Hussein Fakhri Al-Khalidi, rendered the municipality ineffective and frequently threatened to spark serious strife in the city. In 1945, Sir William Fitzgerald, head of Palestine’s High Court Judges, drafted a plan for a new municipal mechanism - the so-called ‘Borough-Plan’. This allowed for the preservation of the city’s unity but suggested separate Arab and Jewish councils be created with a degree of autonomy over respective boroughs. An 11-member British-run administrative council would oversee the elected councils and monitor issues pertaining to shared spheres and holy sites. Fitzgerald held that Jerusalem was indivisible per se but nonetheless presented an outline map for sectoral subdivision along the lines of “an administrative county.” The Jewish borough was to be situated to the northwest of the Old City, while the Arab borough ran north to south with the Old City at its center. With the referral of the Palestine Question to the UN, the premise of retaining British rule over the city was dropped, but the guiding principles of access to, and protection of, holy sites gained their most solid expression. The November 1947 UNGA Partition Plan (Res. 181) called for the creation of a 258 km2 Corpus Separatum under the supervision of a UN Trusteeship Council. Dispensing with the corridor to the coast, the proposed enclave stood to include Bethlehem as well as 17 large Palestinian villages and two main Jewish settlements. Within the Corpus Separatum area an estimated 105,000 Palestinians and 100,000 Jews were to elect separate semi-autonomous municipalities, while the UN was to ensure the area’s demilitarized and neutral status. A UN-appointed governor was to supervise the creation of an international police force and remain responsible for foreign affairs and access to the holy sites. Unlike previous schemes, the plan provided for a plebiscite after 10 years, whereupon the Trusteeship Council would review the situation and issue further recommendations - potentially including partition of the city. The Corpus Separatum plan, along with the Partition Plan as a whole, was no sooner ratified than it was consigned to failure. Violent attacks and counter-attacks on villages within the proposed enclave as well as upon Jerusalem neighborhoods began immediately following the UN vote. On 1 April 1948, Zionist militias stepped up their combined offensives against the villages to the west of the city. On 9 April, at Deir Yassin, a massacre was committed. In all, 39 villages were depopulated around Jerusalem. An estimated 10,000 homes and properties were seized in the city itself, their inhabitants and owners expelled to the east. Only on 15 May did Transjordanian forces enter from the east and prevent the fall of the entire capital. By the time the British, charged with maintaining order and protecting the civilian population, left Palestine (14 May 1948), nearly 85% of municipal Jerusalem had been seized and the process of expelling its remaining Palestinian inhabitants was in its final stages. Already, by February 1948 - barely six weeks after the UNGA approved the Corpus Separatum plan - JA Executive Chairman Ben-Gurion could declare: “From your entry into Jerusalem, though Lifta [a Palestinian village], Romeima [a Palestinian suburb]... there are no Arabs. One hundred percent Jews... in the west one sees not a single Arab; I do not assume that this will change.”

Related Maps

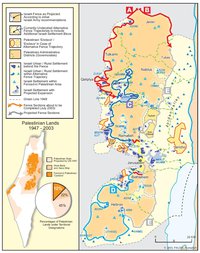

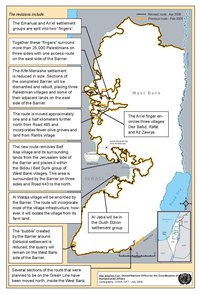

ISRAEL'S SEPARATION BARRIER, 2002

REVISED ROUTE OF THE ISRAELI SEPARATION BARRIER, 2006

THE OLD CITY, 1944 & 1966

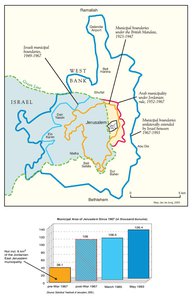

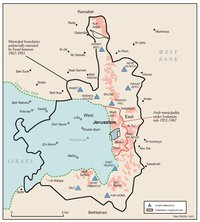

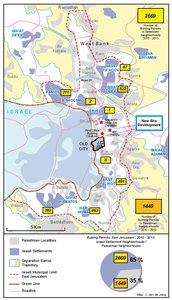

MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES OF JERUSALEM, 1947-2000

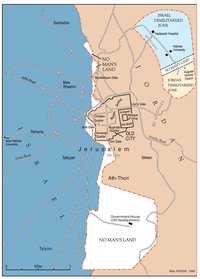

PARTITIONED JERUSALEM, 1948-1967

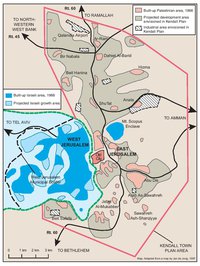

THE KENDALL TOWN SCHEME, 1966

JERUSALEM AFTER THE 1967 WAR

ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS AND PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS IN EAST JERUSALEM, 2000

ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS AND PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS IN METROPOLITAN JERUSALEM, 2000

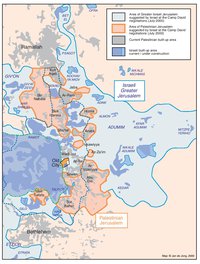

ARAB EAST JERUSALEM WITHIN ‘GREATER’ JERUSALEM, 2000

PROJECTION OF THE ISRAELI PROPOSAL FOR JERUSALEM’S FINAL STATUS AT CAMP DAVID, JULY 2000

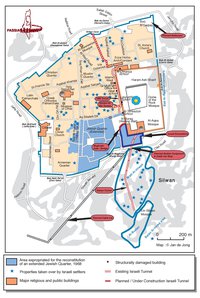

SETTLEMENT ACTIVITY IN THE OLD CITY

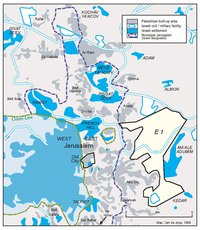

THE E-1 DEVELOPMENT PLAN

THE JERUSALEM MASTER PLAN

JERUSALEM TODAY (2014)